The Da Vinci Code has struck a nerve. When published in 2003, it appeared at the top of best seller’s lists across the nation. On the competitive New York Time’s List, it remained for an astonishing 136 weeks. Within its first year, it sold more than any other adult novel in the history of publishing, and it continues to sell, boasting in the fall of 2005 34 million books in print worldwide.

The books success has not surprisingly spawned a number of investigations. In the fall of 2003, ABC News produced, Jesus, Mary and Da Vinci, a one-hour special devoted to an exploration of the novel’s central claims. A search of Amazon.com reveals dozens of books with titles such as The Da Vinci Code Decoded, Secrets of the Code, Breaking the Da Vinci Code, and Truth and Fiction in the Da Vinci Code, all devoted to dissecting the contents of this single book. If that wasn’t enough, now a movie, the ultimate proof of a novel’s success, is scheduled for release in May. The combined talents of Director Ron Howard and Oscar-winning actor Tom Hanks insure that the popularity of the book has yet to wane.

This phenomenal success cries out for explanation. What is so unique about The Da Vinci Code to cause this pandemic in book sales around the world? Although on the surface the book is merely a novel: a fictional story written for sheer entertainment, its pages contain a very interesting conspiracy.

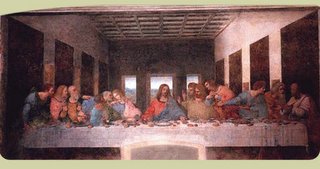

As the title suggests, the paintings of Leonardo Da Vinci occupy a central place within this mystery. According to The Da Vinci Code’s author, Dan Brown, Da Vinci's paintings “seem to overflow with mystifying symbolism, anomalies, and codes… hidden levels of meaning that go well beneath the surface of the text… clues to a powerful secret.” For The Da Vinci Code, Leonardo’s painting of The Last Supper holds the most surprising revelations of all.

At first glance, The Last Supper is a simple depiction of Christ and his disciples. They are seated, facing the audience, behind a long straight table, Jesus separating six disciples on either side of him. Every line of the spacious high-ceilinged room, as well as every gesture, expression or position of the disciples points to Jesus, who looks slightly downward toward his outstretched hand. It does indeed appear as Leonardo claimed that the scene is a representation of the moment at which Christ said to his disciples “…one of you will betray me.” To the right of Jesus, Simon Peter leans past Judas Iscariot to ask, the beloved disciple, who the betrayer might be. To the left of Jesus a disciple asks with inquisitive hands, is it me. Several figures point upwards as if reminding the audience from wince Jesus came and to where he shall return.

According to the Da Vinci Code, the meaning of the Last Supper resides beneath the surface. The book invites us to take a second look, abandoning our preconceived notions about its interpretation or meaning. Is Da Vinci doing more than presenting Christ and his disciples? If this is indeed a representation of the last supper, and the moment at which Christ announces his betrayal then the painting possesses some surprising details. First, the book points out there are thirteen cups littered over the table, not just one, as the gospels appear to indicate. If indeed there was a single distinguishing cup (i.e. the Holy Grail) that Christ passed to his followers, why is it not depicted here? The book answers the Grail is not an object, but rather an individual.

To the right of Jesus sits a person who art historians have long identified as John the beloved. According to John 13, it was John, the disciple whom Jesus loved, who reclined next to Jesus during this crucial moment. A second look, however, uncovers a startling paradox. The individual seated to the right of Jesus lacks the masculine qualities associated with a male disciple. This person has flowing red hair, delicate folded hands, and possibly the hint of a bosom. The seat of honor appears not be occupied by a man but rather a woman.

The figure not only appears to be a woman, The Da Vinci Code argues the very symbolism within the painting demonstrates she is a woman. The absent space dividing Christ and this feminine looking figure makes an unmistakable “V”. The book claims this “V” along with its opposite the “^” are ancient symbols corresponding to woman and man. The “^” symbolizes the hard edge of a man, his warrior instincts as well as his procreative genitals. The “V” on the other hand, symbolizes the soft nature of the woman as well as her uterus, the place within a woman that carries a child. The book argues, to find this indistinguishable “V” proves that the figure seated next to Jesus is in fact a woman.

The symbolic connection between Jesus and this figure also runs deep. If you trace Jesus from his left hand, over his head, down to his right hand, up the left arm of the female figure and once again down over her head, we find that Jesus and this woman together make an unmistakable “M.” Jesus and this woman also are connected by corresponding colors. Jesus wears a blue robe and red tunic. The woman wears a red robe and blue tunic. Visually the corresponding blue and red suggests a bond between Jesus and this person that does exit between Jesus and the other disciples.

This second look at The Last Supper has had a profound impact on the success of the book. Editor Dan Burstein recalls that as he read the book for the first time, he came to this particular section about the painting around 4:00 in the morning. “I got up out of bed and pulled the art books down from our library shelves. I looked at the Leonardo panting that I had encountered, of course, hundreds of times previously, yes, it really does look like a woman seated next to Jesus! I thought.” The fact that a plausible clue has been hidden in one of the most famous paintings of all time is riveting.

Through the clues within this painting, The Da Vinci Code postulates its central conspiracy. According to the book, Da Vinci was a part of a secret society which existed in one form or another down through the ages, extending from a time before the Church transformed the image of Jesus. The Jesus of history married Mary Magdalene, the closest of his female disciples, and through her bore a child. The Church, however, covered this relationship in an effort to proclaim Jesus divine, believing He could not be God if he had sexual relations with a woman. So the male dominated Church abolished Mary Magdalene and the child she bore, along with all reverence for pagan worship of the female image. For the Da Vinci Code, Reclaiming Jesus’ lost bride is a step towards reclaiming the “sacred feminine” abandoned by the Church so long ago.

The Da Vinci Code’s success is its penchant for finding mystery in the mundane. It’s this hidden level of meaning which has inspired the imagination. To a culture hypnotized by ten-second commercials and bill boards passing at sixty miles an hour, the concept of a deeper meaning appears as something novel. Educated as we are in this warp-speed society we are not accustomed to mediating on anything longer then a few seconds. The Da Vinci Code offers a chance to slow down and find vital messages locked within images we simply don’t take the time to look at. The Da Vinci Code has unlocked an all but forgotten world, a world that is only seen through reflection. We want something deeper, something more than surface to sink our teeth into. And thus, gone are Brown’s former books of far removed symbols of the NSA and NASA. Now Brown has placed his mystery within a framework important to everyone and in a context familiar to all. Instead of focusing on complicated mathematical constructs and theories unintelligible and uninteresting to many, Dan Brown has focused on the hidden meaning of art, and not just any art, but some of the most hallmark images known in western tradition, The Last Supper, The Mona Lisa, the Cathedrals of Europe.

Wheres the connection to the Gospel of John? Brown draws upon several books to support his conclusions. A large portion of the book arises from the best selling claims of Holy Grail, Holy Blood. Which attempt at exposing the history of the Priory of Sion was a best seller in the early 1980's. Dan Brown also utilizes The Woman with the Alabaster Jar and the Goddess in the Gospels written by Margaret Starbird.

Starbird, once a devout Catholic, was trained in divinity school. When she read the claims of Holy Grail, Holy blood she set out to discredit them. But in the process she found new evidence within scripture that these claims were true. Starbird points out that the gospels are replete with calling Jesus the bridegroom. Imagery of a wedding also abound. She states “throughout the Gospels Jesus is presented as bridegroom, but it is now widely claimed that he had no Bride.” Among the most startling is a piece of evidence found in the gospel of John.

Only John among the gospels states that the anointing was performed by Mary of Bethany while Jesus was seated with Lazarus on the eve of Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Only John of the gospel writers states that the fragrance of the perfume filled the house where they were seated. This scene seems suprisingly remenesent of Song of Solomon 1:12. “While the king was at his table my perfume gave forth its fragrance.” This reference to one of the most sexually explicit books of the bible raises some interesting questions. Starbird goes on to note that the Church has made another connection between Christ and Mary and the Song of Solomon. Such as reading the Song of Solomon 3:2-4 on Mary Magdalene’s day. A fact that even Hypolutus commented on his commentary on the Song of Solomon.

Though I would disagree with Starbird on many of her conclusions this does not detract from some of the interesting connections she makes. Does John possess hidden clues about Jesus marriage? Is John a riddle on the level of Dan Brown’s interpretation of the Last Supper? Is John like this proposed interpretation of the Da Vinci Painting? Is John a code?

Other than the book of Revelation, no other New Testament book compares with the mystery locked within the gospel of John. John’s gospel says a great deal more than it actually says. Like “body language,” its meaning proceeds through more than just words. What seems clear and simple on the surface is never so simple. John is mystery waiting for the perceptive reader to unlock. If I may appropriate in part the words of Dan Brown, the gospel of John overflows with mystifying symbolism, anomalies, and codes, hidden levels of meaning that go well beneath the surface of the text… clues to a powerful truth. John is mystery greater then paintings of Da Vinci.